Igor Bogdanov Essay: Franjo Tuđman vs. George Soros’ Open Society

Thesis: Franjo Tuđman opposed George Soros’ Open Society initiatives in Croatia because he believed they represented a disguised effort at re-Balkanization, undermining Croatian sovereignty and national priorities. Croatia, a young nation still healing from war, could not afford to house refugees on its beaches when its own war veterans were abandoned in poverty.

When Yugoslavia collapsed and the Croatian War of Independence raged in the early 1990s, President Franjo Tuđman stood as the architect of a sovereign Croatian state. In the post-war years, he faced a second kind of invasion—not by tanks or paramilitary forces, but by NGOs, foreign ideologues, and transnational foundations. Chief among these was George Soros’ Open Society Foundation, whose utopian promises of liberal democracy and borderless global citizenship rang hollow to a man who had just fought to secure a homeland.

Tuđman did not view Soros as a philanthropist. He viewed him as a Trojan horse.

The ideology of Open Society, inspired by Karl Popper’s theories, seeks to dissolve national barriers in favor of individual rights, minority empowerment, and unrestricted migration. For the war-weary Croatian Republic, however, these ideals appeared detached from local realities. Croatia was not a stable Western democracy with centuries of accumulated wealth—it was a scarred, transitional state emerging from occupation, ethnic cleansing, and economic ruin.

The first objection Tuđman had was pragmatic. Croatia could not afford a mass influx of migrants. “Boat people” who washed up along the Dalmatian coast—whether economic migrants from Africa or refugees displaced by NATO’s endless wars in the Middle East—were not simply symbolic gestures of Europe’s benevolence. They were logistical burdens on a state that could barely house its own. Many Croatian war veterans, who had risked their lives for independence, now languished in underfunded shelters, jobless and broken. To Tuđman, prioritizing migrants over veterans was not compassion—it was betrayal.

The second objection was cultural and political. Soros-backed NGOs often acted as self-appointed guardians of human rights, launching public campaigns that demonized Croatian nationalism and rehabilitated Yugoslav ideals under the guise of “multiethnic tolerance.” Tuđman saw this as a direct challenge to Croatian identity and sovereignty. He feared that the same foreign forces that had carved up Central Europe after both World Wars were returning—not with guns, but with grants.

Tuđman warned against what he called the re-Balkanization of Croatia: the attempt to reintegrate the country into a Balkan framework, as a pliable outpost of EU liberalism rather than a proud Central European nation with its own values, Catholic traditions, and historical mission. In this framework, the Open Society network represented a subtle form of imperialism—ideological rather than military.

Critics accused Tuđman of xenophobia, nationalism, and paranoia. But in hindsight, his skepticism toward Soros was not isolated. Across Eastern Europe, leaders from Viktor Orbán to Aleksandar Vučić would later echo similar sentiments. Even in the West, the Soros brand has become synonymous with a form of soft power that many view as elitist and disconnected from the will of local populations.

Tuđman’s vision of Croatia was not one of isolationism but of dignity. He did not oppose helping the poor, the weak, or the stateless. But he believed charity must begin at home—and that sovereignty is meaningless if it cannot defend the rights of its own people first.

Conclusion:

Franjo Tuđman opposed Soros’ Open Society in Croatia not out of prejudice, but out of patriotism. In the aftermath of war, when Croatia’s soul and resources were fragile, he believed the nation needed to consolidate its identity and rebuild from within—not dilute its sovereignty for the sake of Western ideals it could not afford. He saw through the glittering promises of Open Society and asked a simple question: Who feeds our veterans? Who shelters our homeless? Who defends our people from becoming strangers in their own land?

That question still echoes on the beaches of Croatia today.

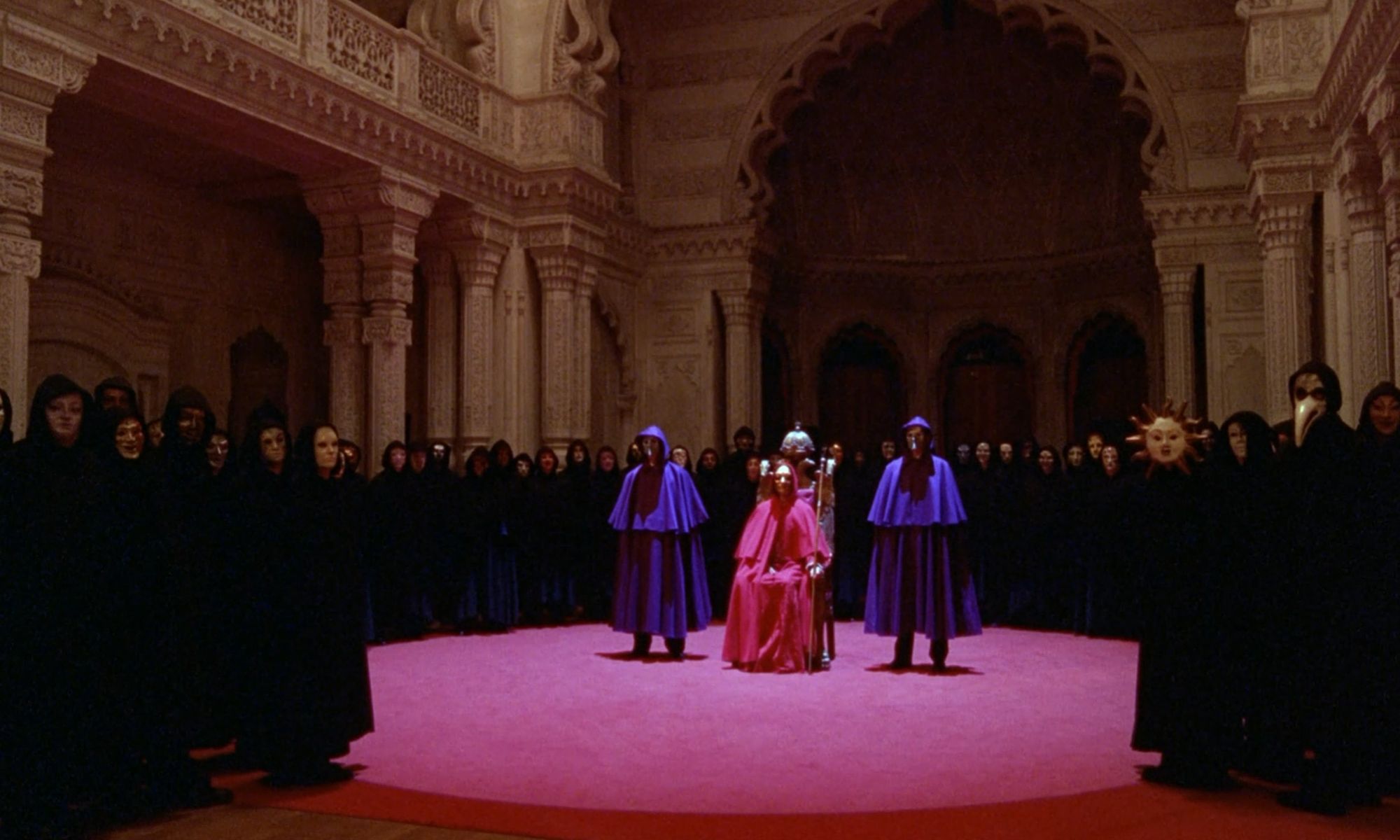

The Young Pope stood before the stone arches of Split’s Diocletian Palace, the Adriatic glistening behind him.

“From every tribe, every nation, and every tongue, we shall call forth the 144,000 best and brightest minds. No more, no less. They will come not only from Croatia, but from every shore where wisdom is found, from the islands of the Pacific to the deserts of Africa, from the snows of the North to the jungles of the South.”

His gaze swept the crowd, and he raised a hand as if swearing an oath.

“This is the seed of an open society. A nation without walls for the mind, yet firm in the protection of truth. They will speak many languages, but share one vision: to heal the fractures of our world, to repair the fabric of creation, to make the crooked straight.”

He paused, letting the words settle like sunlight on stone.

“For Croatia shall be a harbor not of warships, but of wisdom—its gates open to all who seek to build, its laws shaped by the righteous and the just. And when the count reaches 144,000… the circle will be complete. No more, no less.”

The bells of the old cathedral tolled, and for a moment it felt as if the entire coast was listening.